Strathnairn Arts a colourful history

From being granted to famous explorer Charles Sturt (who allegedly lost the land in a card game to Charles Campbell), farmed and built upon by the Baird family, to hosting a range of creative endeavours—and a menagerie of animals—the picturesque precinct of Strathnairn Arts has a history as rich and colourful as the works of art produced there.

From its vantage point overlooking the majestic Brindabella Mountains and undulating pastureland, the Strathnairn Arts Homestead is not only one of Canberra’s best kept secrets, it is the inspiration behind Ginninderry’s brand new suburb, Strathnairn.

It’s a haven for artists and art lovers, with studios for artists working in a variety of visual media. With three gallery spaces that regularly hold exhibitions, a gift shop featuring handcrafted products, a vegetarian café open Wednesday to Sunday, and beautiful gardens to wander through, it’s also an oasis of peace for anyone wanting to retreat to a quiet and beautiful place that seems a million miles away from our city—but in fact is only 10 minutes from Belconnen.

It has also been the setting in which many people’s lives, ambitions, tireless work, losses, heartbreak, joys and passions have played out. Before European settlers claimed the land around Strathnairn, this region belonged to the Ngunnawal people, with evidence of Aboriginal quarrying for dark red jasper in the general vicinity, as well as artefacts made from other raw material.

However by about 1824, the beginnings of Indigenous dispossession were seen as the first European graziers took up grants of land. These settlers included George Palmer who named his property Ginninderra, and the famous explorer, Charles Sturt, who was given 5000 acres in 1837, naming it The Grange.

An anecdote claims that Sturt soon after lost the property in a card game to Charles Campbell, son-in-law of Palmer, but this cannot be verified. What is known is that the transfer of the entire 5000 acres to Campbell occurred on 26 February, 1838.

Campbell renamed the land Belconnel Station; a name that evolved to Belconnen and was eventually given to Canberra’s western satellite town in the early 1960s. Despite having extensive land holdings including Duntroon and Yarralumla, the Campbell family put a lot of effort and expense into the land at Belconnel Station. When Charles died in 1888, his son Fred inherited the land and worked hard to develop it.

He designed and built fences covering a large area, drained swamps and built dams to cater for a merino sheep breeding program and went to considerable effort to control feral pests including rabbits. So it’s not surprising that when the Commonwealth Government decided to claim much of his land as the site of the new national capital, he and his family were considerably distressed. It took three years for the government to finalise arrangements, during which Fred rallied and pleaded with authorities to reconsider. However his pleas fell on deaf ears and not only did he lose Belconnel Station, but also his home, Yarralumla—now the residence of the Governor General.

In 1911, the Belconnen property was acquired by Colonel David Miller, newly appointed Administrator of the Federal Capital Territory, for his own use. He and his family added workers’ accommodations and a laundry to the property and were active in the community until 1923.

From 1924, the homestead was leased to Jack Read, who built a small fourroomed weatherboard house that forms the core of the current homestead and planted around 500 hundred pine trees. David Elphinstone took over the lease in 1931, adding a verandah/sleepout to the eastern side of the house, a living room with a fireplace to the south and a garage to the back of the house.

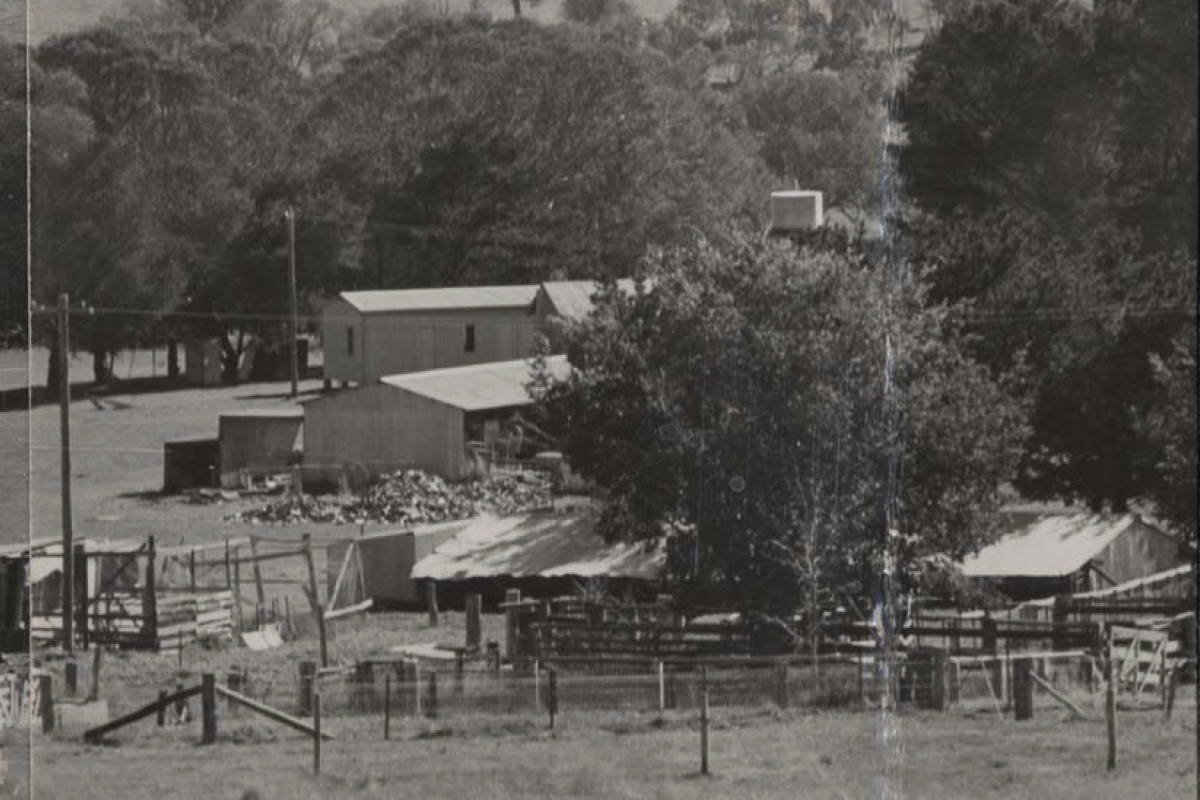

In 1934, the Baird family bought the block, which was now 1126 acres in size. Despite the onset of the Great Depression, they managed to extend the homestead and build the woolshed and other farm buildings, including a cottage, fowl yard, feed store and a shearers quarter. In keeping with their Scottish heritage, they named the property Strathnairn and set about running a farm with sheep, some cattle and horses.

Living 16 kilometres from Canberra, they learnt to be self-sufficient. Ellen Baird kept the large larder at the homestead stocked with bulk food supplies and preserved fruits. Ian tended a bountiful garden for fresh produce, and there was sheep for meat, cows for milk, and chickens for eggs, which was particularly vital during World War II, once rationing was introduced. Electricity didn’t reach the property until 1948, and a consistent water supply was always a challenge.

They were also exposed to the extreme weather conditions with a fire sweeping close by in the 1960s and the sounds of the Murrumbidgee River roaring when it flooded.

Nevertheless one of their sons, David Baird, recalls a happy-go-lucky childhood. ‘We ran free all over the place’ said David. He and his brother, John, shared adventures with the two Anderson boys from neighbouring Pine Ridge. David remembers the family hosting dances and parties in the woolshed, playing tennis on their court, and competing in polo games at the Canberra Showground.

David eventually took over the lease from his father in 1965, running both merino sheep and varieties of Shorthorn cattle until the property was resumed by the Commonwealth Government in 1973, marking the end of an era.

After a few years of temporary leases, the Blue Folk Community Arts Association was granted a 25-year lease on the Strathnairn homestead and 23 acres of land, by the Department of the Capital Territory in 1980.

The family hosted dances and parties in the woolshed, played tennis on their court, and competed in polo games at the Canberra Showground.

Made up of a group of artists, actors, poets, singers and musicians, they aimed to promote, manage and conduct festivals of music, drama, and theatrical productions for both children and adults.

It was a demanding program for the fledgling committee and its five full‑time staff, with much of the responsibility shouldered by the Artistic Director, Domenic Mico (Founder of Canberra’s Multicultural Festival), who lived with his family at Strathnairn. Along with his creative work, he also undertook general maintenance activities and the care of the animals— four goats, two horses, chickens, geese and ducks, a peacock, doves, a donkey named Pedro, and some sheep.

They received several grants for construction works and their programs, and volunteers enthusiastically contributed to working bees to develop the grounds and facilities. And, according to Domenic, the programs were nothing like what you would be allowed today, with activities including sword fighting, launching a pirate ship into the dam and rounding up ‘convicts’ in carts.

Despite Domenic resigning to pursue studies in Italy in 1981, Blue Folk continued to conduct programs such as farm visits, dramatic productions, exhibitions, weekly classes, school activities, holiday programs and workshops for the intellectually disabled.

However, the huge workload and maintenance of the property became an ongoing problem and the drought in 1982 took its toll, not just on the land—but for the Blue Folk budget that was drying up.

In 1984, Blue Folk changed its name to Brindabella Community Arts in the hope that it would revitalise the organisation. The name change, however, did nothing to alleviate the problems or the dwindling budget, and—despite the huge personal effort of volunteers and several managers, resulting in renovations and new programs—by 1992, the association had a mere 13 dollars in its account.

Nick Stranks and Alison Munro came on board at this time and, together with Caretaker Michael Sainsbury, they attempted to turn the situation around. They spent considerable time cleaning up neglected studios that had become infested with rats and possums, and inundated with mould.

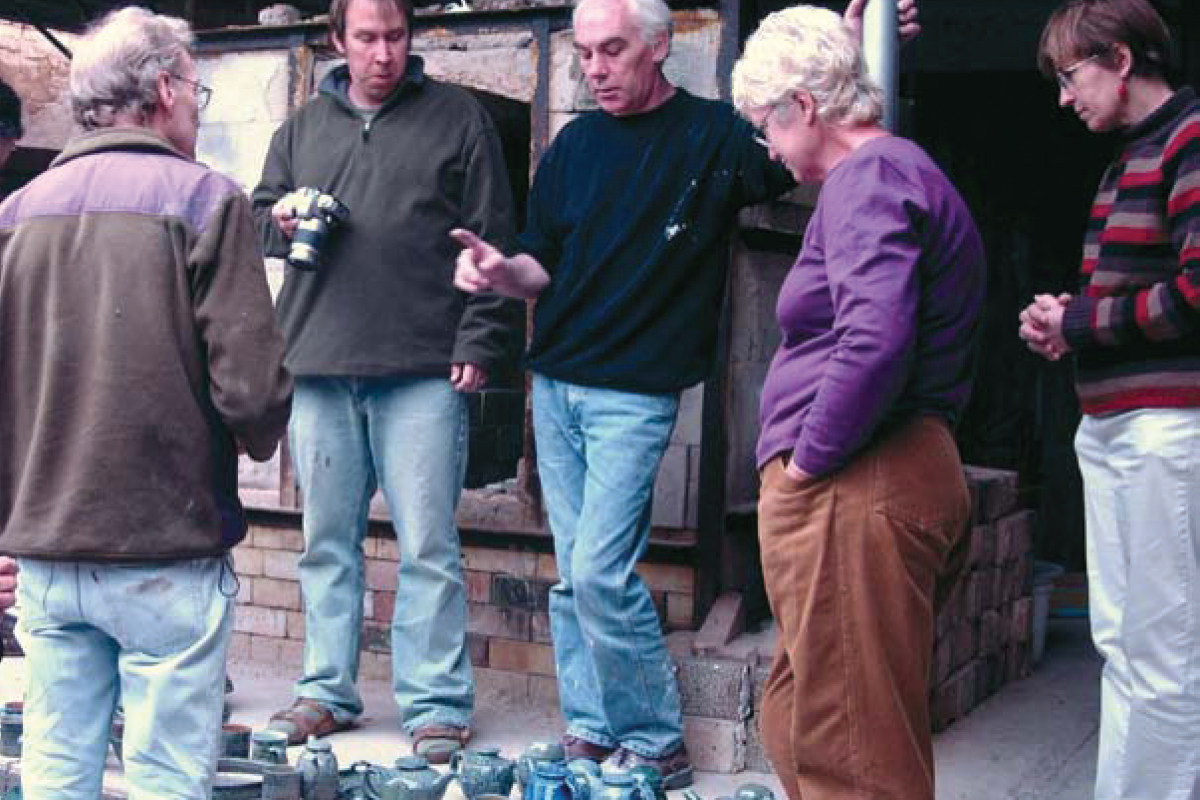

They then encouraged students to exhibit at Strathnairn and invited Alan Watt, the Head of Ceramics Workshop at the (then) Canberra School of Art, to use the studios for some of his ceramics students. Alan accepted on the basis that his department would have ‘exclusive rights to some studios and were able to build kilns in a purpose-built shed,’ which led to the formation of the Strathnairn Ceramics Association.

Because of the funding and organisation, ceramics quickly became the dominant art medium at the property and a kiln shed was built, and workshop space extended through the enthusiastic efforts of volunteers and art students.

Strathnairn’s profile was raised through activities such as the sponsorship of a School of Art ‘Emerging Artists Support Scheme’, that offered a studio residency and exhibition to the selected recipient. Eventually, Brindabella Arts Association and the Strathnairn Ceramics Association merged to become an almost entirely self‑sufficient entity—finally metamorphising into the Strathnairn Arts Association in 1998.

Passionate people continue to be at the heart of Strathnairn today. An active Board, a small team of professionals and dedicated volunteers contribute to what it is now; a vibrant community with engaging facilities for the general public to enjoy, a thriving arts facility, and an integral part of Canberra’s heritage.

Facts and stories from the publication Strathnairn – A place for People, available for purchase at the Strathnairn Arts Homestead SHOP.