Breathe Easy – A Northbourne Avenue Study

Since 2011 Riverview Group has proudly supported the ACT Young Canberra Citizen of the Year Awards and sponsored the Young Environmentalist Award.

In 2017 Ginninderry’s Community and Cultural Planner, Susan Davis first met Ben Maliel, the recipient of a High Commendation at the ACT Young Canberra Citizen of the Year Awards 2017. After recently connecting again Ben shares with Susan what he’s been up to and shares details of his work on the Canberra Light Rail development.

My name is Ben and in 2017 I finished Year 12 at Canberra Grammar School (CGS).

Last year, I received a High Commendation at the ACT Young Canberra Citizen of the Year (YCCY) Awards 2017. I received this award for my work in establishing a student-led sustainability initiative at our school, called Sustainable CGS, to raise awareness about sustainability and the environment. As a founding member of the group, I led the implementation of the group’s flagship initiative – campus-wide recycling. This included the investigative phase, development of the proposal, design of a business case, securing funding, and the implementation and evaluation of the program. This project was very successful and has resulted in around 20,000 litres of recyclables being diverted from landfill every school term.

When Susan and I reconnected earlier this year the topic of one of my school projects came up in our chat, and Susan thought it would make for a good read on the Ginninderry website – hence this blog post.

Environmental Systems and Societies was one of the subjects I took as part of my International Baccalaureate Diploma Program at Canberra Grammar. The major piece of internal assessment for this subject required a scientific investigation to answer a self-chosen research question. As urban planning and transport have always fascinated me, I thought I’d work on a project that investigated ozone levels and trees in the context of Canberra’s Light Rail development – which at the time (early 2017) was just beginning.

How important are the Northbourne trees?

The early stages of the Light Rail development involved the somewhat controversial clearing of the River Peppermint gum trees lining Northbourne Avenue. I noticed that the trees were being cleared in distinct sections, leaving stretches of road with trees and stretches without. This was a great opportunity to study what role these trees played in keeping air pollution in check. Following some serious thinking and workshopping, I formulated my research question:

Do trees reduce the amount of ground-level ozone in the air around Northbourne Avenue?

What next?

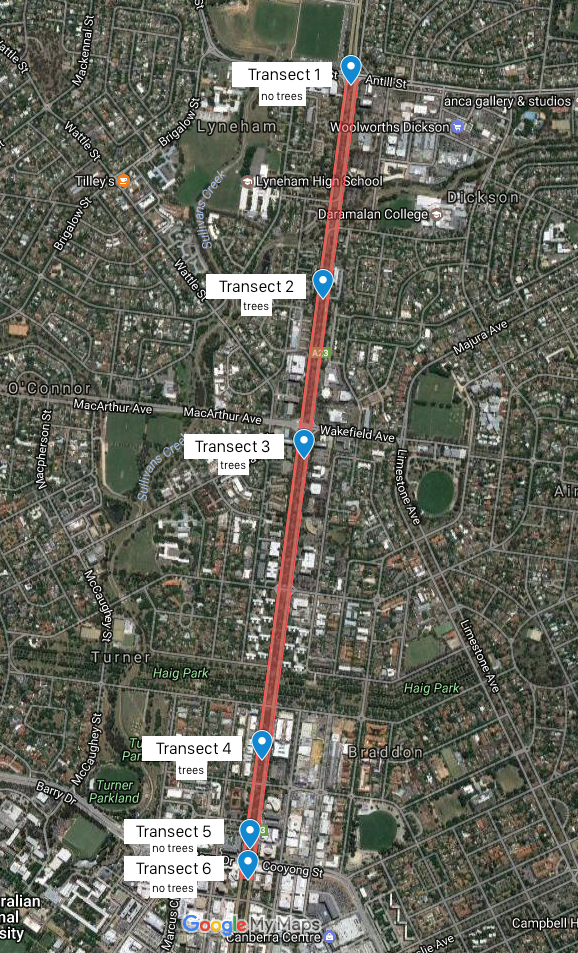

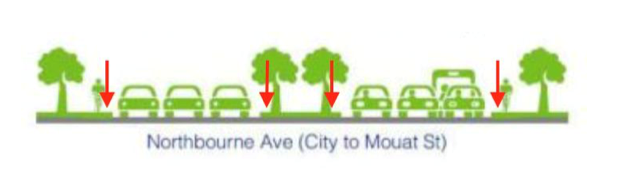

I chose the road corridor extending from the Northourne Avenue – Mouat Street – Antill Street intersection southwards to the Northbourne Avenue – Rudd Street – Bunda Street intersection as my study area (see Figure 1). To have a reliable study, I set up a total of 24 sampling points using the grid sampling method. The sampling points were grouped along six east west transects – three transects in sections with trees and three in sections without trees. Each transect had four sampling points – two on either side of the northbound road and two on either side of the southbound road (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Study area: The road corridor along Northourne Avenue from the Mouat Street – Antill Street intersection to the Rudd Street – Bunda Street intersection.

I distributed the sampling sites like this to make sure I got an accurate representation of the study area and avoided potential skewing of the results by factors such as traffic conditions, wind direction and sunshine. Buses, for example, travel in the left lane which could possibly increase pollution on that side of the road.

Figure 2. A graphic representation of the four sampling points along each of the six transects.

Figure 3. An example of a road section with trees.

Figure 4. An example of a road section without trees.

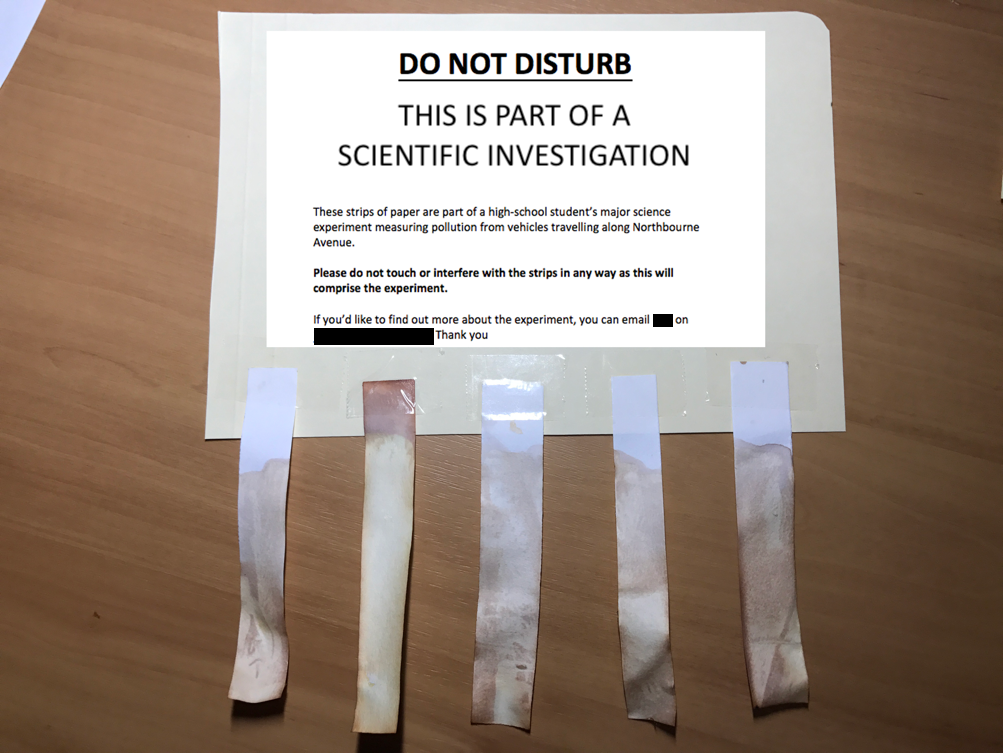

Having worked out the sampling method, I researched the best way to measure ground-level ozone (GLO) and found that I could buy high-tech ozone samplers. Perfect… or maybe not, as each sampler would cost several hundred dollars. After some more researching, I found out about a GLO measurement method using the Schoenbein paper. This method suited my study as it is both effective and inexpensive. The Schoenbein paper changes colour depending on the concentration of ozone in the air surrounding it. I then set about making the Schoenbein paper strips at the school lab. It was a long day, applying a potassium iodide mix on each strip by hand and drying them in an incubator.

Figure 5. Hand-made Schoenbein paper strips (active ingredient potassium iodide)

Figure 6. A Schoenbein ozone card including a note to the public, ready for installation at a sampling point

Next came the exciting part of setting up the study material in the field. Armed with a stack of Schoenbein ozone measurement cards and sticky tape, my parents and I set out at 4 am one cool February morning to beat the morning peak hour and set up the sampling sites (and make sure that I got to Rowing training on time at 5:45 am!).

After leaving each sample card out for 12 hours, it was time to reverse the morning’s process and collect all the sample cards.

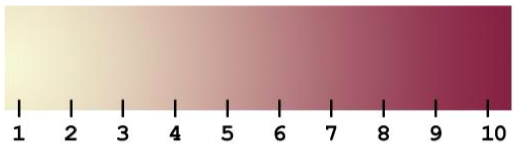

Once I was back home, I used the Schoenbein Index (see Figure 7) to assign a score to each paper strip based on its colour.

Figure 7. Schoenbein Index (Source: Chemistryland.com)

Using the average Schoenbein numbers from the 24 sampling points I worked out the amount of ozone in the air.

My findings

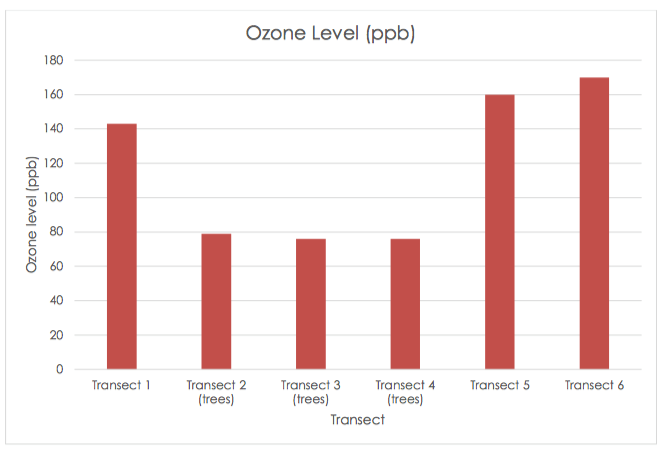

I was excited by the results as they were very definitive. They showed that the average ozone level in sections where there were no trees was more than double that in sections with trees The results show that trees do play a significant role in reducing ozone levels.

Figure 8. Graph of average ozone level at each transect

So where to from here?

This local scale study can be applied more broadly in the context of the environmental issue: atmospheric pollution by greenhouse gases. The findings of my experiment show that trees do have the potential to significantly reduce GLO pollution in urban centres. It is also well-known that plants significantly reduce carbon dioxide levels in the atomosphere. The investigation shows that trees can be used as a management strategy, on a local scale, to solve the broader environmental issue of atmospheric pollution. The results provide a foundation for local urban planners to invest in the planting of trees in urban centres, especially in areas with high pollution levels.

Back to Northbourne Avenue, the good news is that Canberra Metro has committed to establishing roughly 30% more trees once Stage 1 is complete – so we won’t have to hold our breath for too long, soon we’ll be breathing even cleaner air!